The Archipelago's Strategic Reassessment and Regional Support Initiatives

Alexandre Sancan is a student in the Peace, Humanitarian Action and Development Masters program at Sciences Po Lille. He specializes in the study of the security and economic dynamics of the Indo-Pacific region, with a focus on Japan.

This work aims to study Japan’s strategic reconfiguration in the Sahel region following the In Amenas incident, in 2013. This terrorist attack compelled the Abe administration to undertake a series of initiatives intertwined with new laws and frameworks aimed at strengthening Japan’s security capabilities.

This shift translated into:

- A security-oriented aid approach: this trend was first observed at the TICAD V when Japan committed to providing $1.3 billion in development aid to strengthen the surveillance system of the Sahelian countries. This aid began to increase following the adoption of the Development Charter (2015), with a concentration on enhancing border control and capacity building.

- The New Approach for Peace and Stability in Africa (NAPSA): adopted in 2019, this framework provides Japan with a comprehensive security framework to address the root causes of conflict resolution.

- Increasing contribution directed through multilateral organizations: a means for Japan to overcome the worsening security context of the Sahel while maintaining a presence in the region. However, France’s withdrawal and the conclusion of MINUSMA have hindered Japan’s aspiration to step up its involvement in ensuring peace and stability in the region.

Japan’s extraordinary economic development in the twentieth century incentivized Japanese political leaders to use this power to increase their influence on a global scale, including in Africa regarded as a source of raw materials and a hub for further regional economic expansion. This perception led Japan to progressively embrace a neo-mercantilist approach characterized by the growing use of development aid to penetrate African markets (Schraeder, 1999). As a result, the distribution of grant aid allocated to the continent accounted for 27.4% in 1994 and has consistently hovered around this figure ever since (MOFA, 1994). With the Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD) launch in 1993, Japan has progressively become a major player on the African continent.

Yet, Japan’s engagement has faced serious challenges in the last years. On the first hand, Japan has struggled to bounce back from the “lost decades” following the collapse of an asset bubble in the early 1990s. This prolonged period of low growth led Japan to cut its spending on Official Development Aid (ODA) from 1994 until 2015, when the country began to increase its budget again (OECD, 2024). On the other hand, the decline in both humanitarian and security conditions over the past decades, especially in the Sahel, compelled the international community, including Japan, to reevaluate its involvement in the region. The US, the EU institutions, Japan, Germany, and the UN World Food Program have been the leading contributors to ODA in the Sahel, accounting for 75% of what the region received between 2002 and 2014 (Laville, 2016). Traditionally more focused on economic and social infrastructure assistance, Japan’s approach underwent a new shift after the attack launched by an Al-Qaeda-affiliated organization on the Tigantourine gas facility near In Amenas (Algeria) in January 2013. This event prompted the Abe Administration to update Japan’s identity as a leading donor of ODA to redefine a framework and build tools to address the various threats in the region.

Strategic shifts in the region and their consequences on Japan’s stance

In 2013, Japan’s approach underwent two significant changes. At the national level, the Abe Administration introduced the policy of “proactive contribution to peace”, approved by the Cabinet as the first National Security Strategy (NSS). This transformation in Japan’s security doctrine aimed to overcome legal roadblocks to enhance the archipelago’s defense capability and revitalize its domestic defense industry (Sasaki, 2023). At the regional level, the government of Japan adopted a 3-pillar foreign policy in response to the In Amenas incident. These three pillars focus on “strengthening counter-terrorism measures, enhancing diplomacy towards stability and prosperity in the Middle East, and [providing] assistance in creating societies resilient to radicalization” (MOFA, 2015). Over the past decade, the adoption of these intertwined policies has led Japan to increase its involvement in the Sahel region through non-military means.

The restructuring of Japan’s foreign policy in Africa has increasingly shifted its focus on development assistance towards a more security-oriented aid approach. Embodied by the last presidents of the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA), this new trend was first observed at the TICAD V in 2013. During this conference, Japan committed to providing the Sahel with $1.3 billion in development aid to help strengthen surveillance systems as well as the stability of eight Sahelian countries (Chad, Niger, Mali, Mauritania, Cameroon, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, and Senegal) (Sasaoka et alii, 2022). The same year, Japan started to send police officers from Africa, including Sahelian countries, to undergo training at its National Police Agency as part of its support of conflict prevention and mediation efforts. From 2013 to 2018, more than 140 African police officers were trained in Japan (Najah, 2022). Japan’s engagement went further with the adoption of the Development Cooperation Charter in 2015, allowing the archipelago to assist foreign armed forces in achieving non-military objectives. Following the adoption of the Charter, the aid allocated to enhance the security capabilities of the Sahelian states began to increase, with a concentration on strengthening border control (through the provision of information and communication technology) and capacity building in areas of humanitarian assistance and UN-mandated peacekeeping operations (UNPKO) (Sasaoka et alii, 2022).

However, Japan’s expanding engagement has been mostly indirect, in the form of financial contributions and capacity-building assistance. Under the impetus of the Abe Administration, Japan aimed to become a serious stakeholder to ensure peace and stability in the region. In Africa, this objective materialized through the adoption of the New Approach for Peace and Stability in Africa (NAPSA), which frames Japan’s strategy with the TICAD 7 pillars adopted simultaneously in 2019. The NAPSA highlights Japan’s aspiration to address the root causes of conflict resolution by playing the role of prevention (institution building, human resource development, etc.) and mediation (peacebuilding activities) (Uesu, 2022). Moreover, it provides Japan with a comprehensive security framework that demonstrates its stance after the withdrawal of most of the Self-Defense Forces (SDF) from South Sudan in 2017 (Morreale, 2019). For instance, Japan took part in the Sahel Coalition, alongside France and the U.S., to bolster capacity-building assistance in Sahel countries and continue conducting training initiatives in legal, police, and security domains (Yonetani, 2021). In addition, the archipelago joined the Alliance Sahel as an observer to strengthen cooperation with its Western allies. Finally, Japan’s engagement in the Sahel went one step further in 2019 when the country joined the G5 Sahel as an observer.

Embracing multilateralism to proactively contribute to peace in the region?

In 2020, Japan’s bilateral ODA accounted for approximately 81.1% of overall disbursements, while ODA’s contribution to international organizations accounted for approximately 18.9% (MOFA, 2021). This significant contrast underscores Japan’s focus on strengthening relations with recipient countries, fostering its image as a leading donor of development assistance. According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan (MOFA), ODA’s contribution to international organizations allows the archipelago to maintain its presence in a deteriorating humanitarian and security context (2021).

In the Sahelian context, there has been an inverse trend and Japan’s security contribution has been increasingly directed through the UN and its specialized agencies. On one hand, Japan increased its contribution to UNPKO deployed in the region. For instance, Japan was the second-largest support to MINUSMA in terms of funding, allocating approximately $100 million annually from 2013 to 2016. Furthermore, Japan also contributed to the UNPKO in South Sudan (UNMISS) with the deployment of a unit of SDF. Initially, tasked with engineering work in 2011, their mandate evolved progressively towards security-related duties to include civilian protection (2014) and “rush and rescue” missions (2016) (Pajon, 2017). On the other hand, the archipelago increased its contribution to projects implemented by UN agencies, targeting mainly two areas: one is border management (by IOM[1]In 2024, Japan disbursed $32 million to support a wide range of operations implemented by the IOM, with more than half of this contribution dedicated to supporting vulnerable people affected by … Continue reading) and prevention of violent extremism (by UNDP), and the other is emergency humanitarian assistance (by UNHCR mostly) (Sasaoka et alii, 2022). Most of the Japanese-funded projects focused on peacebuilding, counter-terrorism, and economic recovery, are implemented in collaboration with the UNDP.

Japan’s quest to expand its presence in Africa also relies on partnerships with third countries. Facing a lack of knowledge of the Western African areas, coupled with the scarcity of French-speaking Japanese, Japan has sought to reinforce its relations with France as a means of addressing these gaps (Antil, 2019). Both countries have led coordinated actions in the Sahel, focused on capacity building of police forces and juridical systems (Senegal, Chad, Nigeria, Mali, Niger, Burkina, Mauritania) border control (Mauritania), and communications equipment for security agencies (Niger) (Pajon, 2017). France looked to scale up this collaboration by benefiting from Japanese assistance in its Sahel Cross-Border Cooperation Assistance Program, but Japan did not respond to this invitation, highlighting its challenge in departing from its traditional low-key approach to security matters in the region (Pajon, 2022).

The evolving security dynamics in the central Sahel have significantly influenced Japan’s strategic orientation. MINUSMA ceased to exist at the end of December 2023 and France was driven out from central Sahel, making way for other powers to fill the vacuum. Furthermore, there is no longer cooperation with the G5 Sahel due to the dissolution of the alliance announced by Chad and Mauritania after the withdrawal of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger between 2022 and 2023. These shifts have constrained Japan to step back from its goal to gradually enhance its presence through multilateral organizations or third countries.

Today, only a few Japan-funded projects have been developed in the Central Sahel regarding peace and stability. A continuation of the project initiated in 2020 to strengthen capacity building for the PKO School in Bamako has remained and is focused now on supporting the Mali Peacekeeping School to strengthen conflict prevention and management capacities of ECOWAS countries (UNDP, 2023). Furthermore, a partnership between JICA and UNESCO was signed in May 2023 to implement programs for the prevention of violent extremism and the empowerment of youth and women in Mali. Finally, JICA has recently started a project on capacity-building and decentralized level administration in the Sahel countries focusing on Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali[2]Confirmed in an interview with an Advisor at the JICA, March 8, 2024, by videoconference..

Facing challenges in demonstrating its efficacy in the central Sahel, Japan has progressively shifted its strategic focus towards less risky yet more economically important areas, such as Senegal, where numerous projects are already underway. Nevertheless, the initiatives undertaken by other external major powers, such as China and Russia, prompted Japan to keep seeking tools and options to maintain its influence in the region.

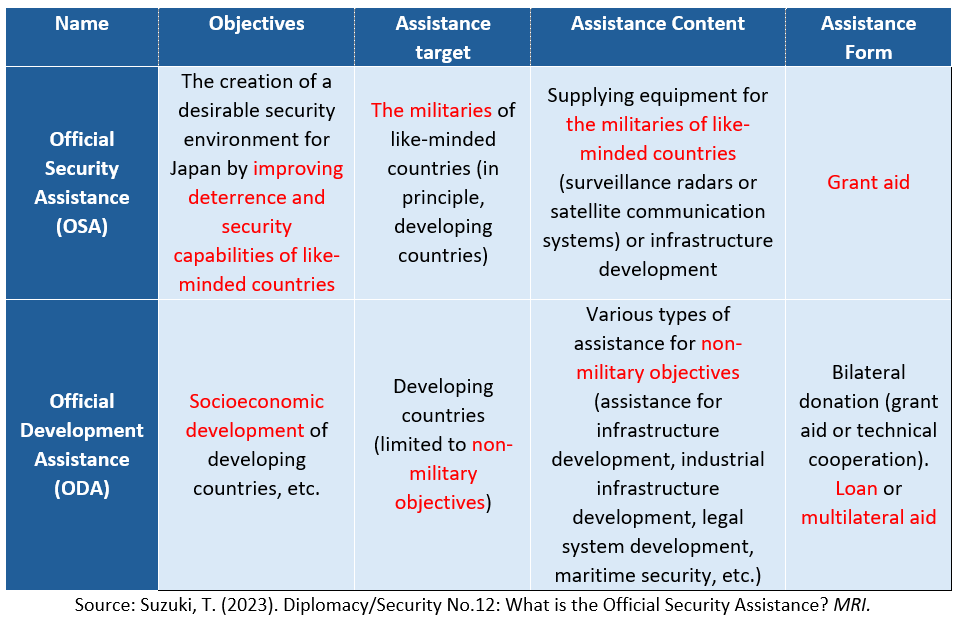

The adoption of a new cooperation framework called “Official Security Assistance” (OSA) as the new “National Security Strategy” in December 2022 confirms Japan’s aspiration to restrict China’s military and economic influence by stepping up its involvement in ensuring peace and stability on a global scale (Nishida, 2023). The framework of OSA embodies activities previously encompassed by ODA such as providing surveillance radars, satellite communication systems, and infrastructure development. As depicted in the chart below, the OSA aims specifically to support the militaries of like-minded developing countries, a significant difference from the ODA, which is officially restricted to non-military objectives. Still in its experimental stage, this new framework once again highlights the Japanese government’s prioritization of security over development. It remains to be seen whether the OSA framework will be implemented in the future to restore the archipelago’s connection with the security landscape in the Sahel.

Differences between OSA and ODA[3] Chart translated from Japanese by the author

Notes

| ↑1 | In 2024, Japan disbursed $32 million to support a wide range of operations implemented by the IOM, with more than half of this contribution dedicated to supporting vulnerable people affected by conflicts and disasters in Sub-Saharan Africa (Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Kenya, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Niger, and Sudan).

|

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Confirmed in an interview with an Advisor at the JICA, March 8, 2024, by videoconference. |

| ↑3 | Chart translated from Japanese by the author |

Antil, A. (2017). Japan’s Revived African Policy. Éditoriaux de l’Ifri. IFRI.

Laville, C. (2016). Les dépenses militaires et l’aide au développement au Sahel : quel équilibre ? Working Papers No. 174, FERDI.

MOFA (2015). 3-Pillar Foreign Policy in Response to the Terrorist Incident Regarding the Murder of Japanese. Available at: https://www.mofa.go.jp/press/release/press3e_000031.html

MOFA (1994). Overview of Japan’s Economic Assistance to the African Region. Available at: https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/oda/area/africa/over.html

MOFA (2021). White Paper on Development Cooperation 2021, Japan’s International Cooperation. Available at: https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/oda/white/2021/html/index.html

Morreale, B. and Jain, P. (2019). Japan’s new model of Africa engagement. East Asia Forum, [online]. Available at: https://eastasiaforum.org/2019/09/06/japans-new-model-of-africa-engagement/

OECD (2024). Development co-operation profile: Japan.

Pajon, C. (2017). France and Japan in Africa : a Promising Partnership. Lettre du Centre Asie No. 71. IFRI.

Pajon, C. (2017). Japan’s Security Policy in Africa: The Dawn of a Strategic Approach? Asie.Visions No. 93. IFRI.

Sasaoka, Y., Aimé, R. S. T. and Uesu, S. (2022). Perspectives on the State Borders in Globalized Africa. Routledge.

Sasaki, R. (2023). Japan’s Path from Arms Export Ban to Promotion. E-International Relations. https://www.e-ir.info/2023/11/15/japans-path-from-arms-export-ban-to-promotion/

Schraeder, P. J. (1999). Japan’s Quest for Influence in Africa. In Current history (1941) (Vol. 98, Number 628, pp. 232–234). Current History, Inc.

Suzuki, T. (2023). Diplomacy/Security No. 12: What is the Official Security Assistance? Mitsubishi Research Institute.

UESU, S. (2022). Toward a new approach for stabilizing the Sahel and West Africa; A short review of Japan’s security assistance since 2013. IGPSA.

UNDP. (2023). Support the Mali Peacekeeping School to strengthen the conflict prevention and management capacities of ECOWAS countries, [online]. Available at: https://open.undp.org/projects/01000443

Yonetani, K. (2021). La contribution du Japon en faveur de la paix et la stabilité dans la région du Sahel. Ambassade du Japon en France, [online]. Available at: https://www.fr.emb-japan.go.jp/itpr_ja/11_000001_00266.html

Alexandre Sancan, "Japan in the Sahel after the In Amenas Attack. The Archipelago's Strategic Reassessment and Regional Support Initiatives". Journal du multilatéralisme, ISSN 2825-6107 [en ligne], 13.08.2024, https://observatoire-multilateralisme.fr/publications/japan-in-the-sahel-after-the-in-amenas-attack/